THE FLAW IN ALL AUTO-FOCUSING CAMERAS

or

WHY AUTO-FOCUSING CAN NEVER ACHIEVE TRUE

ACCURACY

WITH MOST SUBJECTS

©2006 Mark B. Anstendig All

auto-focusing cameras have a fatal flaw which can never be corrected and which

will prevent them from ever achieving true focusing accuracy with most

photographic subjects. Many of the auto-focusing devices in these cameras are

based on the principles of the “Messraster”, an invention that can achieve

absolutely exact focusing. But the auto-focusing versions will never be able to

duplicate the accuracy of the original invention.

The Messraster, which is the only known device that is able to

achieve focal-point-exact focusing accuracy with all subjects and in all

picture-taking situations, was introduced in

To

understand the importance of the fact that no auto-focusing devices can achieve

precise results, one must first understand that much of what has been believed

to be true about focusing and depth-of-field is proved wrong when it is

possible to place the plane of focus exactly where it is wanted with

millimeter-exact (focal-point-exact) precision. Early in photography, there was

a mistaken belief in optics about how the light rays approached the

focal-point. Instead of a nearly infinitesimally narrow sharpest plane of focus

(focal-plane), it was believed that there was a certain distance within which

everything was equally sharp. Contrary to these early beliefs, good-quality

lenses do achieve resolution essentially equal to a point. True

focal-point-exact focusing can, therefore, be achieved and there are noticeable

and very important differences in every other aspect of a photograph if the

location of the exact plane of focus (focal-plane) is changed even small

amounts.2 In a portrait, for example, there will be a distinct,

noticeable, and important difference if the focal -point is placed exactly on

the pupil of the eye or if it is placed even a few millimeters in front or in

back of the eye.3 This holds true even when the lens is stopped

down.

It

is also very important to understand that, because, physically, there can only

be one sharpest distance from the lens, depth-of-field does not describe

sharpness. It, in fact, describes varying degrees of unsharpness.

Depth-of-field is simply a set of subjective guidelines that try to tell you

how far in front or back of the focal plane the unsharpness will remain

tolerable. There still remains one precise distance from the lens that will be

sharper than all other distances and, more important, only at that distance

will the other aspects of the subject--color tones, size relationships,

etc.--be accurately reproduced. The Anstendig Institute possesses comparison

photographs, made with the Messraster, that prove this and other related points

made in this paper.

If

it is accepted that even small changes in the location of the focal-plane will

change the appearance of the photograph, it follows that the photographer

should be able to place that focal-plane anywhere with pin-point accuracy. It

also follows that, once focusing has been achieved, it is imperative not to

change the distance of the camera to the subject until the exposure has been

made. Therein lies the ultimate, crucial flaw in all auto-focusing systems, a

flaw that can never be eliminated: in all auto-focusing systems, the focusing

sensors are located in the center of the viewing area.4 There are

two basic ways such a centrally located focusing system can be used, and both

result in unavoidable focusing errors with all subjects except those that are

flat and parallel to the camera.

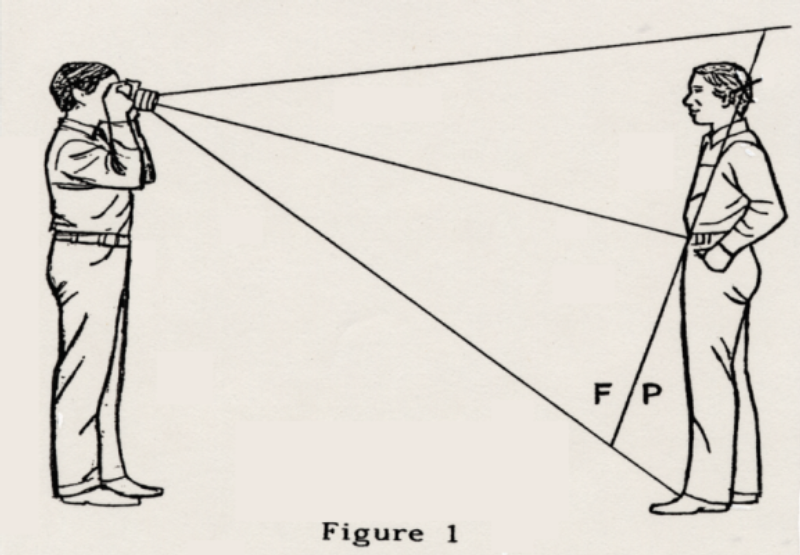

In

figure 1, it is clear that, if the subject is well framed, the auto-focused

lens will be focused on the front of the subject's body. But our institute's

demonstration photographs, made with the Messraster, show that the point that

should be precisely in focus is the subject's nearest eye. If the lens is

focused so that the focal-plane is exactly on the pupil of that eye, the whole

picture will take on a quality called "plasticity" (the effect of

three-dimensionality on a two-dimensional surface), the apparent depth-of-field

will be greater, and there will be less impression of graininess. The

expression of the subject will be more accurate and the photograph will come to

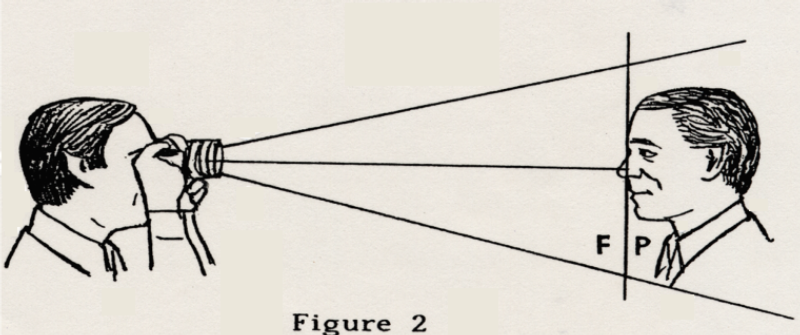

life in a very special way. Figure 2 shows that, in a portrait which includes

only the head, the auto-focus will be on the nose or mouth area, both of which

lie much farther forward than the eyes. Comparison photographs show that, in

addition to the above-mentioned effects, placing the focal-plane in front or in

back of the eye will change, i.e. falsify, the expression.

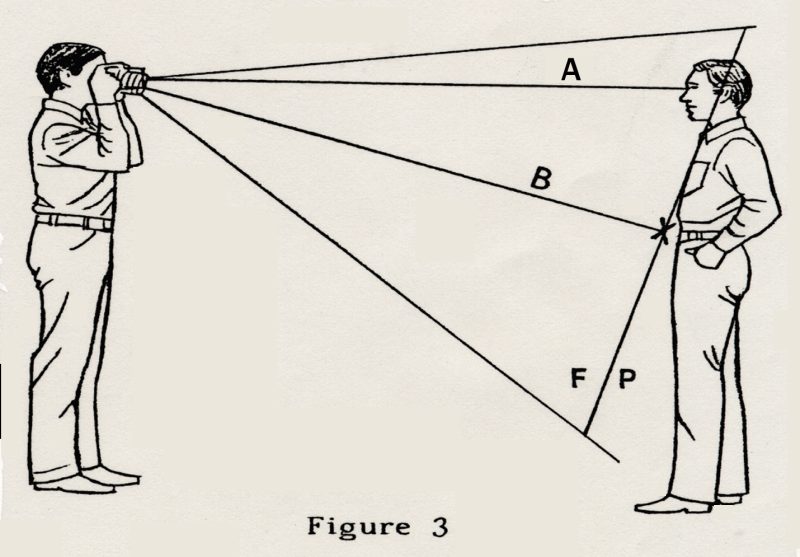

A

second way auto-focusing could be used would be similar to using focusing aids

in the center of a ground-glass screen. First the center-focusing area of the

screen would be placed on the most important point in the picture. When

focusing has been achieved, a button would lock the focusing mechanism. The

picture can then be framed and taken, without changing the lens setting. But

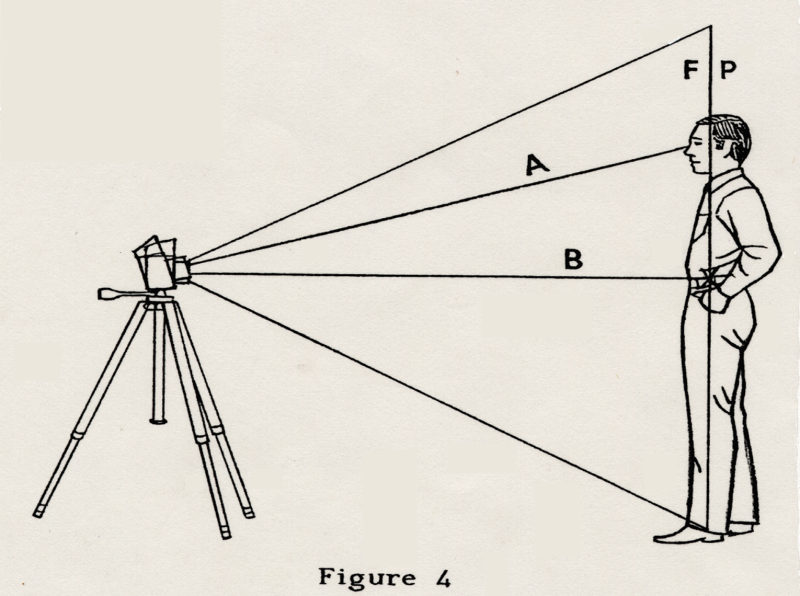

figures 3 and 4 show that, if the angle of the camera is changed after the

focusing has been achieved, the subject-to-camera distance is also changed and

the focus will no longer be on the desired subject point. The fact that, in

figures 1, 3, and 4, the picture will be focused too far back adds to the

misfortune. The important subject point will end up in front of the focal plane

and there is less apparent depth-of-field in front of the focal-plane than

behind it.5 If there must be a focusing error, it would be better to

err towards front-focusing than back-focusing. All manual focusing systems that

are located in the center of the ground-glass suffer from this same built-in

error because of the inability to focus and frame the picture simultaneously.

Another

flaw in current auto-focusing devices is that the measuring area is too large.

The systems measure an area of the subject that is about as large as the

center-circle of most focusing screens. Figure 5 shows that, with most

subjects, this area includes many differing distances. Which one is the sensor

measuring? The nose is far forward and the eye, where the focus should be, is

far back. The sensor can only measure an average for the whole area and the

focus will probably be somewhere around the eyebrows and not on the eye. This

flaw can be overcome by making the measuring area tiny. A measuring area the

size of a dot in the exact center of the screen would solve the problem. But

the problem of precisely focusing on a subject-point without having to change

the angle of the camera to frame the picture can never be solved.

The

only practical location for the focusing area in auto-focusing is the center of

the viewing area. That is the only location that allows both horizontal and

vertical use. Therefore, with any auto-focusing system, focusing and framing

cannot be achieved simultaneously and changing the camera-to-subject angle in

order to frame the subject more precisely automatically changes the focus. This

built-in shortcoming of all auto-focusing makes it impossible to achieve any

focusing precision in the bulk of picture-taking situations.

Something

has to be wrong when a focusing system is brought out on the market in

extraordinarily complex, expensive versions that can never be accurate, but the

simplest and cheapest-to-make version, which can achieve absolute accuracy with

all subjects no matter where the subject is located in the viewfinder, is

suppressed. It should be emphasized that it is the focal-point-exact focusing,

not how it is achieved, which makes the big difference in picture taking and

determines the outcome of all other elements of the picture.6 If any

photographers have other means of achieving absolutely accurate placement of

the plane of focus wherever one wants it, they do not need the Messraster. But

no other available device offers anything approaching the Messraster's

accuracy.

Photographers

should be provided with some means of placing the precise plane of focus

anywhere they want it, whether or not they choose to use it. Without that

ability, all picture-taking is pure chance and no one can be sure of the final

result. That is the present state-of-the-art in all photography. Even the most

expensive cameras, with jewel-like precision in all other technical aspects,

cannot precisely locate the plane of precise focus.

Since

the Messraster is the only known patent that lays claim to absolute,

focal-point-exact focusing precision and is no more difficult to manufacture

than most SLR focusing screens, it should finally be made available to those

who care about controlling all of the elements in their photographs. The reason

it has not been made available is that it would invalidate much of today's

technology and make many clear the truth about many present systems, such as

auto-focusing, in which billions of dollars have already been invested.

Some

people will, of course, still place the ease of operation of auto-focusing

above any real focusing accuracy. But, many would change their minds if they

knew the truth. There will always be people who want to achieve the best

possible results. Those people are being let down by an industry that could

provide such a means, but, instead, propagates old, wrong information which

camouflages the failings of their focusing systems.

1 The

Anstendig Institute's papers on focusing describe the "Messraster",

describe why focal-point-exact focusing makes a great difference when one can

achieve it, explain the history of the Messraster and make clear why it was

kept off the market.

2 The Anstendig Institute's papers explain in detail that there is

a great difference in any photograph when the plane of exact focus

(focal-plane) is changed even a small amount and that every other aspect of the

photograph, including the impression of three-dimensionality (plasticity), the

rendering of color tones and the apparent graininess, changes when the placement

of the focal-plane is changed.

3 When the face is turned so that the eyes are not at equal

distances to the camera, the focus should usually be placed on the nearest eye.

4 While it is conceivable to have more than one, switch -selectable, focusing area in the viewing area,

manufacturing such an arrangement would be extremely difficult. The limit would

probably be three focusing areas, in the center, upper and lower picture areas.

Such an arrangement, while better than one area, would still not match the

flexibility of the Messraster and operating such a system would probably be

confusing. The extra operating problems would obviate any advantages of

auto-focus.

5 Depth-of-field relationships are approximately 1/3 in front and

2/3 in back of the focal-plane.

6 The Anstendig Institute's papers give detailed explanations why

all other picture elements are determined by the placement of the focal plane.

In

all illustrations, the plane of focus is labled FP, for focal plane.

Figure

1: If the whole figure is framed, the center-focusing section will be on the

man's belt. The plane of focus will be far behind the eyes.

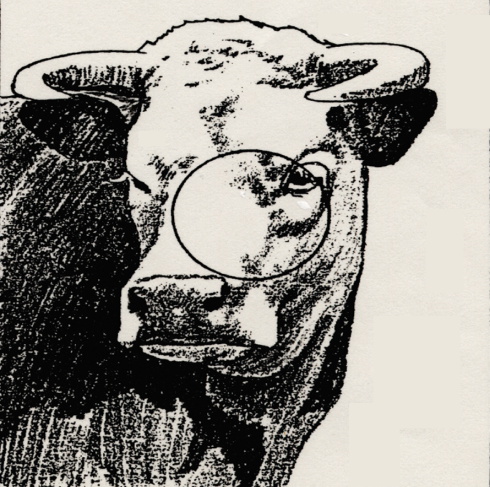

Figure

2: If the head is framed for a typical portrait, the center-focusing section

will be on the nose, i.e., the plane of focus will be too far forward. (See

Figure 5)

Figure

3: (Lines A and B are the same length.) First focusing

is accomplished and locked in place while the center-focusing section is on the

eye (line A). Then, when the picture is framed (line B), the plane of focus

will be in front of the subject's waist, but behind the eyes.

Figure

4: This is the same as Figure 3 with the camera at a lower angle. On the body,

the plane of focus is farther back. But it is also too far back on the head.

Figure

5: This is the same as Figure 2, but from the front. Obviously, many differing

planes of distance are being read simultaneously by the auto-sensor (nose,

mouth, eyes, etc.).

The Anstendig Institute is a non-profit, tax-exempt, research institute that was founded to investigate stress-producing vibrational influences in our lives and to pursue research in the fields of sight and sound; to provide material designed to help the public become aware of and understand stressful vibrational influences; to instruct the public in how to improve the quality of those influences in their lives; and to provide the research and explanations that are necessary for an understanding of how we see and hear.

|